The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau appears to have lost an opportunity to correct a nagging issue in its definition of a qualified mortgage.

The current rule provides safe harbor protection to lenders from potential litigation brought by borrowers for loans having debt-to-income ratios of 43% or less. A proposal in June by the CFPB to replace the 43% DTI limit with a rate-based definition of a qualified mortgage still misses the mark by a country mile. A far more accurate measure of a borrower’s ability to repay their mortgage would be to target the most risk-layered loans in the market as unqualified for safe harbor treatment.

At the heart of the issue is a borrower’s ability to repay their mortgage. The 43% limit was far too simplistic a representation of a borrower’s ability to repay their loan, since it focused on only one aspect of the borrower’s risk profile. What CFPB continues to ignore is the holistic approach to credit evaluation; namely the 3 C’s of mortgage underwriting. Beyond a borrower’s capacity, or ability to repay the loan are credit and collateral.

The credit factor usually measured by credit score and its components is traditionally viewed as an indication of the borrower’s willingness to repay. Collateral, the third C, focuses on the borrower’s skin in the game. When underwriting a loan, all three factors are considered along with others.

Where borrowers get into real trouble is when lenders layer one risk on top of another. For example, lending to a borrower with a 620 FICO score, a 43% DTI and a 100% loan-to-value ratio technically would meet the QM standards, but there is still a great potential for the loan to default due to the confluence of multiple risks; poor credit, high debt load and no equity.

The latest CFPB proposal for QM suggests that imposing a limit based on the prime rate plus 150bps is sufficient to capture the overall risk of a borrower. And economic theory and empirical studies show that higher rates are indicative of higher credit risk. The problem with that view is that the mortgage rate is an endogenous variable, i.e., it is itself determined by the 3C’s of underwriting. So, by that logic, why not simply tie QM to processes used ubiquitously across the mortgage market, namely an automated underwriting scorecard?

After all, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and FHA use such scorecards extensively in making credit decisions every day. Applying a technique well known in the markets for credit evaluation makes sense, is easy to implement and, most important, provides a more accurate representation of a borrower’s ability to repay.

Although credit scores tend to be associated with a borrower’s willingness to repay, they can also be thought of as an indication of a borrower’s ability to handle debt. The linkage between demonstrating knowledge regarding how to manage credit as provided by financial counseling and improving credit has been made by several studies over the years. Compounding a low FICO borrower’s lower ability to handle repayment with a disincentive to repay the obligation with low down payment loans and a relatively high DTI does not help this borrower stay in their home.

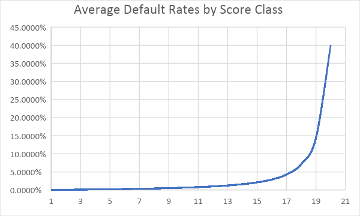

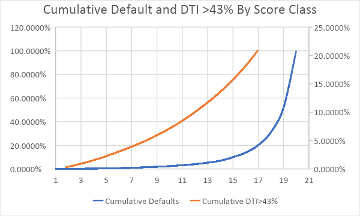

A statistically based underwriting scorecard leveraging the GSEs’ loan level historical credit data can provide a much clearer path forward on defining QM loans. I took a sample of 250,000 loans originated by the GSEs between 2000-2015 and built such a scorecard using FICO, LTV, DTI and several other property, loan and borrower risk factors used to underwrite borrowers. The results are shown in the two graphs below. The 250,000 loans were grouped into 20 equal-sized categories and their average default rates (defined as loans 180 days past due or worse) shown in the top graph.

Clearly, the worst scoring 5% of loans (appearing in the 20th bucket) are far and away significantly riskier than the rest. And looking at the second graph, that worst 5% of loans accounts for more than half of all defaults in the sample and more than a fifth of all loans with DTIs greater than 43%. Average FICOs in this group were 670 compared to the median of 748, and LTVs and DTIs were also significantly higher than the median borrower indicating considerable risk layering for the worst-performing scored loans.

Most of the borrowers in the riskiest scoring group never had a chance to keep their loan as lenders piled risk factor on top of risk factor to make the loan. Originating loans to borrowers with poor or marginal credit, low or no downpayment and high debt burdens is a recipe for a lawsuit down the road. You can’t see this issue by using DTI alone or the prime rate plus 150 basis points as the measure of a qualified mortgage.

CFPB needs to rethink their definition of a QM loan to be better aligned with industry underwriting. A borrower’s ability-to-repay a mortgage cannot be distilled to a single underwriting factor such as DTI or one defined by some spread over the prime rate. Both are somewhat arbitrary limits meant to be reasonable reflections of what a qualified mortgage should be, but in the end fall woefully short of describing the multiple factors that drive a borrower’s ability-to-repay. Using a mortgage underwriting scorecard for GSE and FHA mortgages would provide a more suitable definition for defining qualified mortgages.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of HousingWire’s editorial department and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Clifford Rossi at crossi@umd.edu

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Sarah Wheeler at swheeler@housingwire.com

The post The CFPB missed a chance to fix the QM rule appeared first on HousingWire.