This is the third and final part of an account I wrote as Redfin’s CEO about what it has been like to run a publicly traded company hit hard by the pandemic. This part is about how a furlough and a layoff affected our culture, and where we stand now. The first part, published two days ago, was about our dawning recognition of the pandemic. The second was about how we scrambled to keep our business open.

March 31 – April 3: The Furlough Decision

When we closed our offices, we started broadcasting a company meeting every week via video, ending each with a question-and-answer session. In the first meeting after the office shut-down, on March 12, the number-one question was:

Could the Coronavirus shutdown result in layoffs for Redfin employees?

My answer: “There’s no guarantee that any business can make.” At every company meeting thereafter, the #1 question would be about layoffs.

In January and February, we had about 25% more demand than our own employees could serve. But by that March 12 meeting, instead of being at +25% demand, we were -25%.

At the next week’s meeting, on Thursday, March 19, we addressed layoffs head-on. We showed hypothetical graphs of housing demand. If it looked like demand was going to be in the dumps for just three months, we’d be willing to lose $50 million, and hold on to every employee.

But if it looked like the downturn was going to last for six months or more, we explained, the cost of keeping everyone on would exceed $100 million. And then, we’d have to let people go.

The hard part was that we had to decide on the layoff in April. Every week that we waited to make a decision was costing us $1 million.

Two days after that company meeting, on Saturday morning, March 21, I sent the execs an outline of three possible scenarios: no layoff at all, a 20% cut, and a 40% cut; a 40% cut was added last-minute, as an almost-outlandish worst-case scenario.

Our HR leader, Anne Hatcher, sized up that latter scenario, and said the earliest we could be ready was April 7, a Tuesday just more than two weeks out. We’d long ago recognized that a company our size couldn’t be great at anything without a great HR team. Now that team would come through for us in spades.

That we held out the possibility of no immediate cuts at all may seem delusional, especially now, but it was the scenario our chairman, Bob Mylod, was arguing for every time he and I talked. We used to connect once a month, but now we were on the phone every day. Bob sent me pictures of the Starbucks CEO on CNBC promising not to lay a finger on anyone’s job for 30 days. He told me you’ll be surrounded by people calling for action and blood, and the first rule is “do nothing.”

It wasn’t what I expected from him. Bob had become the chief financial officer of Priceline after the dot-com crash, when it was a sixth-tier online travel agency; he led one layoff, then another, then another; he championed lower commission rates so the firm could take market share and become the most valuable online travel agency in the world, worth more than $100 billion. He was a staunch advocate for keeping costs and prices low.

But Bob had gone to our annual kickoff and met our agents, the ones we employed through thick and thin. And he’d become convinced that what was most valuable about Redfin was the partnership between our agents and our software engineers, so that we could work together to make a real estate sale more efficient. “Don’t pull that apart now,” he’d tell me, “Not at the first sign of trouble.”

But by the last week of March, demand had fallen to a level that could only keep about 65% of our agents busy. And on Friday, March 27, the federal government agreed to add $600 a week to state unemployment insurance. This meant that 75% of our field employees could expect to get more money from the state than from us, because now their sales bonuses were drying up.

For weeks, our chief technology officer, Bridget Frey had been advocating that we furlough agents instead of laying them off, with health-care benefits, and a promise to bring everyone back on September 1. “When the market recovers,” she said, “we’ll need them.” Now, staring down the barrel of a 40% layoff, we embraced Bridget’s proposal.

At 9 a.m. on Tuesday, March 31, the board met to review our plans. The execs recommended to the board a large across-the-board layoff, and a furlough of another 30% of our agents; the total cut was still about 40%, which only a week before had been an outlandish worst-case scenario.

We agreed to severance of between six weeks and four months for laid-off employees, depending on tenure, and a payment of $1,000 for furloughed employees. At Bob’s insistence, we kept a core team of recruiters to help our departing colleagues apply for unemployment benefits in every state.

We told the engineering managers how deep to cut, and on Wednesday, April 1 they came back with a different proposal: reduce our pay instead. Bridget argued that to get our agents back, we’d have to virtualize the whole brokerage. “Stuff that was supposed to take years now has to be done in months,” she said. We’d need almost every engineer we could get.

But I worried that limiting layoffs in a few headquarters departments would split our culture. At the worst possible time, I was full of second thoughts. I woke up at 3 a.m. on Friday morning, April 3, still undecided. I spent an hour writing a letter to the execs explaining a decision I hadn’t even made, to avoid significant layoffs in favor of pay cuts and a furlough.

Since our head of sales, Karen Krupsaw, was on the East Coast, I could call her right away to ask if our agents would understand cutting headquarters pay in lieu of a major home-office layoff. There was a long pause on the line. Maybe Karen was calculating the field’s reaction, or maybe she just knew the importance of ratifying a decision. “Yes,” she said. “It’s hard. But they’ll understand.” I emailed the letter to the rest of our execs.

April 6: The Day Before

I sent this note to an old friend:

I’m sleeping in the attic, because [my wife] Sylv can’t get sick, and working all the time, because we’re about to do a massive furlough, which I’ve been grieving about, more even than I would’ve thought.

Then I had this dream that I was skiing in California, alone. The moguls were melting because of global warming, and the run was hard.

You were waiting at the bottom in that car that we used to call the Millennium Falcon. You were young, like we were when we first became friends & we saw each other every day, but I was the age I am now.

I apologized for being so old and you said it was ok. I didn’t know how to explain myself, what I had become, the thing I was worried about doing. You handed me a giant bag of Tostitos, opened it up, and said just eat, and we drove home.

April 7: The Day Of

At 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday, April 7, I sent another email, this one to the whole company. It began: This email is confidential. I’m very sorry to say that it’s the email that we’ve been dreading. It announced that many employees would be furloughed, some would be asked to leave for good, and most headquarters employees earning more than $85,000 per year would have our pay cut.

Like many recent emails, it had my cell phone number at the bottom, now with encouragement for anyone to call between 5:30 a.m. and 11 p.m. As soon as it was sent, managers on the East Coast began working through their lists of people to contact, starting with the ones who had to go, then reassuring the rest later in the afternoon.

We scheduled a Zoom broadcast for 9:15 a.m. I was still working on the slides a few minutes before the call. The moment I started talking, my phone began buzzing with messages from employees. I picked it up to turn it off and I saw a message from a woman in San Diego who said she had canceled her wedding for the company, and now was being let go.

I spent the rest of the day talking and texting with employees, starting with the first person who’d texted me. I talked to an agent beloved by his entire team. Then a person with epilepsy who had been let go at other companies before. Then someone who’d just had a baby. Then, at the end of the night when I thought it was all over, an agent who once helped me to buy my own home.

This was what I’d expected and deserved. What was unexpected, and far more common, was the barrage of messages, mostly from people leaving the company, saying thank you: for giving them a shot, or telling it to them straight, or really thanking Redfin for no good reason. It was an almost-religious grace that made my commercial considerations feel a little obscene.

We gave anyone being furloughed the option of getting laid off for good, with the same 6 – 16 weeks of severance laid-off employees got. Of the 1,139 being furloughed, 108 took it. Many who opted in to the layoff called to say they wished they hadn’t had to, but a family member was sick or also out of work. These were the ones who had more obligations and fewer reserves, and they were asking me to remember if they ever re-applied that this wasn’t the choice they wanted to make. “We’ll remember,” I said. And we will.

One woman called the day after the furlough announcement, on April 8, at 5:45 a.m, telling me to get a pen so I could write down the names of the amazing people who trained her (Stevie Tibbs, Doug Owens). An Oklahoma manager sent an email describing how nervous she was to tell an employee that the employee was going on furlough:

I centered my thoughts, focused my courage, and began to speak. But she asked, “how can I help?” She said, “It’s my turn. It’s my turn to be a roaring fan, my turn to cheer you and the team on; it’s my turn to rally. It’s my turn to be the 12th man. I’m here with you standing on the sidelines, loud and proud, and I will be ready to jump back in.”

One of our top agents, Hazel Shakur, told us that her Prince Georges, Maryland team had given itself a new name. It had been called “Gorgeous Prince Georges,” but until we had enough sales to bring everyone back, the team was “The PG Avengers.”

A graphic designer named Lindy Kanand began circulating an image of a tiny, undaunted Redfin knight, advancing under the banner of Bring Them Back.

And on Zoom calls across the company, the employees who would remain made themselves part of a collective art exhibit, spelling out messages that they sent to the colleagues leaving that Friday.

I’m not proud that we furloughed some people and laid off others. It should be clear at this point how helter-skelter our execs were, and how limited our foresight was. No company going through this would wish it on anyone else.

But now we know something about ourselves that we could never have been sure of before, about the unshakable decency of the people who once worked at Redfin and of those who still do. They’re better than any business deserves. It has made me wonder if our country, after a fractious, destructive decade, will come out of this pandemic more aware of our own strength.

Epilogue

It’s now Sunday, May 10. A lot has changed since I wrote this piece over the weekend of April 11 – 12. We waited to publish it until after our Thursday, May 7 earnings call. But starting almost from the week this diary leaves off, demand has improved for four straight weeks. We just told investors that seasonally adjusted home-buying inquiries were now at 96% of their pre-pandemic level in January and February.

This may seem like a miraculously complete recovery, but it’s lopsided: from April 2019 to April 2020, the number of homes for sale in the U.S. has fallen 25%. Demand from home-sellers is still way off. We now expect to run out of homes to sell in many markets, possibly as early as this month. If more listings don’t debut soon, bidding wars could become widespread this summer.

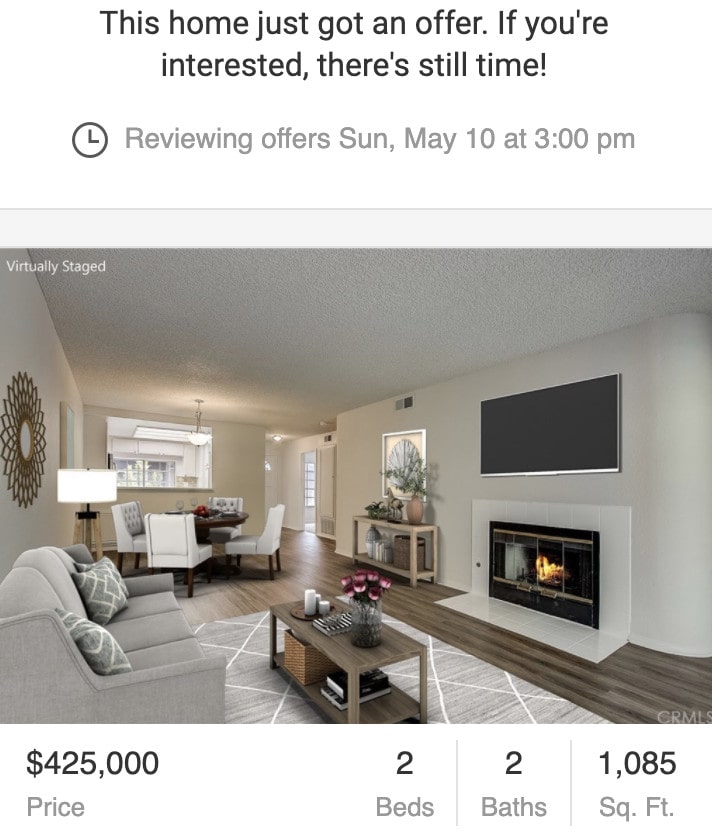

That’s one reason we announced last Thursday that we were starting to buy homes again as an i-buyer. Yesterday, I got a “last-call” email from Redfin.com prompting me to bid on a listing I’d visited online many times over the past month: it was that condo I’d agreed to buy when its owner broke down in tears; what triggered the email was an offer on the condo that we got over the weekend.

The offer was for $450,000, which is $20,000 more than we expected when RedfinNow first bid on the home.

But the most important development from yesterday was the return of 131 employees from furlough. The Saturday before, on May 2, we brought back our first 139. That’s a total of 270 down, and 745 to go before the furlough ends on August 31.

One of the people coming back from furlough, Allie Taylor from Loudoun County (“LoCo”) west of Washington D.C., texted me this image:

It’s hanging on my home-office wall.

There’ll be plenty of work for Allie and everyone else here to do. When this pandemic ends, America will be on the move again, as many folks get leeway from employers to leave big cities for smaller, more affordable towns, in what could be a historic migration. Homebuyers won’t have to tour homes on phones anymore, but many will anyway, because it’s so easy, and the online experience is now so immersive. That means plenty of homes are going to change hands, and the technology Redfin’s now building can make those exchanges easier and less expensive than ever before.

I wish you could meet the people for whom those changes have already begun: the customers we’re serving now aren’t waiting on this pandemic to move on with their lives. So much has gotten less important over the past two months, but maybe homes have gotten moreso. The pictures below are from folks who closed with Redfin agents Shelby Weaver and Jordan Hammond in just the last few weeks.

I think Redfin’s going to be OK.

All the folks pictured or mentioned in this account approved their appearance. Many more rallied to pull Redfin back from the brink. I feel equally grateful for you all.

The first and second parts of this diary are here.

The post Diary of a Pandemic, Part 3: The Furlough (And the Un-Furlough) appeared first on Redfin | Real Estate Tips for Home Buying, Selling & More.